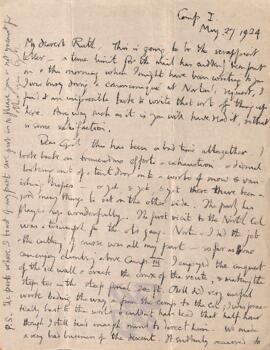

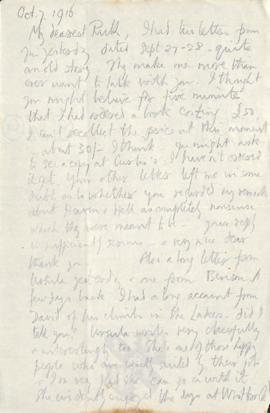

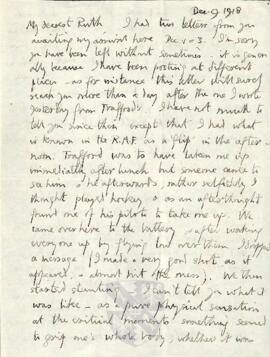

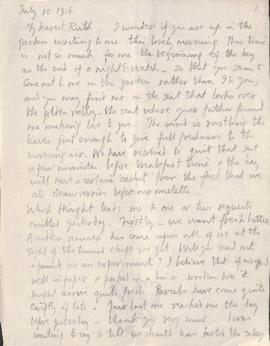

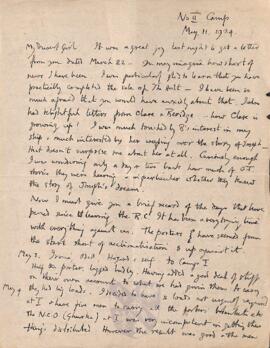

Letter from George to Ruth Mallory from No. II Camp, Everest

Full Transcript

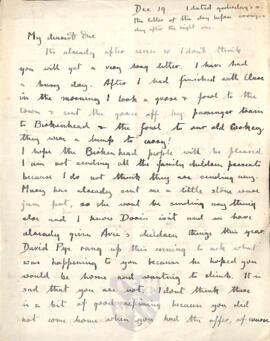

My dearest girl,

It was a great joy last night to get a letter from you dated March 22 – you may imagine how short of news I have been. I was particularly glad to learn that you have practically completed the sale of the Holt – I have been so much afraid that you would have anxiety about that. I also had delightful letters from Clare and Beridge – how Clare is growing up! I was much touched by B’s interest in my ship and much interested by her weeping over the story of Joseph – that doesn’t surprise me about her at all. Curiously enough I was wondering only a day or two back how much of O.T. [Old Testament] stories they were hearing and in particular whether they knew the story of Joseph’s dream.

Now I must give you a brief record of the days that have passed since leaving the B.C. It has been a very trying time with everything against us. The porters have seemed from the start short of acclimatisation and up against it.

May 3 Irvine, Odell, Hazard and self to Camp I

Half the porters lagged badly. Having added a good deal of stuff on their own account to what we had given them to carry they had big loads. I decided to leave 5 loads not urgently required at I and have five men to carry all the porters blankets etc.

May 4 The N.C.O. (Ghurkha) at I was very incompetent in getting these things distributed. However the result was good and the men must have gone well. Irvine and I had gone on ahead and reached II at about 12.30; we had hardly finished a leisurely tiffin when the first porters arrived. Camp II looked extraordinarily uninviting although already inhabited by an N.C.O. and 2 others in charge of the stores (150 loads or so) which had already been carried up by Tibetans. A low irregular wall surrounded a rough compound, which I was informed was the place for the sahibs tents, and another already covered by the fly of a Whymper tent was the home of the N.C.O. The sahibs compound was soon put sufficiently in order, two Whymper tents were pitched there for the four of us while a wonderful brown tent of Noel’s was pitched for him. No tents were provided here for porters the intention was to build comfortable huts or ‘sangars’ as we call them using the Whymper fly’s for roof, but no sangars had yet been built and accomodation for 23 men is not so easily provided in this way. However I soon saw that the ground would allow us to economise walls & Irvine and I with 3 or 4 men began building oblong sangar, the breadth only about 7ft; other men joined in after resting. It is an extraordinary thing to watch the conversion of men from listlessness to some spirit of enterprise; a very little thing will turn the scale; on this occasion the moving of a huge stone to form one corner started the men’s interest and later we sang! And so these rather tired children were persuaded to do something for their comfort – without persuasion they would have done nothing to make life tolerable. Towards 3.0 pm Odell and I (Irvine seemed tired after prodigious building efforts) went on to reconnoitre next day’s march over the glacier. We began by going along the stones of the true left bank, the way of 1922, but the going was very bad, much more broken than before. To our left on the glacier we could see the stones of a moraine appearing among the great ice pinnacles. We gained this by some amusing climbing retraced our steps a little way along it towards Camp II and then on the far side reached a hump from which the whole glacier could be seen rising to the south; from a point quite near us it was obvious that there could be no serious obstacle and that point we saw could be gained in a simple way: it only remained therefore to make a good connection with Camp II. We followed easily down the moraine, which is a stony trough between high fantastic ice pinnacles and a beautiful place and just as were nearing camp found a simple way through the pinnacles – so in an hour and a half the first and most difficult part of the way from II to III had been established.

4th to 5th An appalling night, very cold, considerable snow fall and a violent wind.

5th Result – signs of life in camp – the first audible ones in camps up to and including II are the blowing of a yak dung fire with Tibetan bellows – on the 5th these signs were very late.

The men too were an extraordinarily long time getting their food this morning. The N.C.O. seemed unable to get a move on and generally speaking an oriental inertia was in the air. It was with difficulty in fact that the men could be got out of their tents and then we had further difficulty about loads; one man, a regular old soldier, having possessed himself of a conveniently light load refused to take a heavier one which I wanted taken instead; I had to make a great show of threatening him with my fist in his face before he would comply and so with much argument about it and about, as to what should be left behind as to coolie rations and blankets and cooking pots and the degree of illness of 3 reporting sick we didn’t get fairly under way until 11 am. Now making a new track is always a long affair compared with following an old one – and on this occasion snow had fallen in the night. The glacier which had looked innocent enough the evening before was far from innocent now. The wind had blown the higher surfaces clear, the days I suppose had been too cold for melting and these surfaces were hard, smooth, rounded ice, almost as hard as glass and with never a trace of roughness, and between the projecting humps lay the new powdery snow. The result of these conditions was much expenditure of labour either in making steps in the snow or cutting them in ice and we reached a place known as the trough – a broad broken trough in the ice 50 ft deep about 1/3 of the way up knowing we should have all we could do to reach Camp III. Accordingly we roped up all the men in 3 parties; this of course was a mere device to get the men along as there isn’t a crevasse in the glacier until rounding the corner to III. We followed along in the trough for some way a lovely warm place, and then came out of it onto the open glacier where the wind was blowing up the snow maliciously. The wind luckily was at our backs until we rounded the corner of the North Peak – and then we caught it, blowing straight at us from the North Col. As the porters were now nearly exhausted and feeling the altitude badly our progress was a bitter experience. I was acting as lone horse finding the best way and consequently arrived first in camp. It was a queer sensation reviving memories of that scene, with the dud oxygen cylinders piled against the cairn which was built to commemorate the seven porters killed two years ago. The whole place had changed less than I could have believed possible, seeing that the glacier is everywhere beneath the stones. My boots were frozen hard on my feet and I knew we could to do nothing now to make a comfortable camp. I showed the porters where to pitch their tents at 6.0 pm; got hold of a rucksack containing 4 china cookers, dished out 3 and meta for their cooking to the porters and 1 to our own cook: then we pitched our own two Meade tents with doors facing about a yard apart for sociability. The porters seemed to me very much done up and considering how cold it was even at 6.0 am I was a good deal depressed by the situation. Personally I got warm easily enough; our wonderful Kami produced some sort of a hot meal and I lay comfortably in my sleeping bag. The one thing I could think of for the porters was the high altitude sleeping sacks (intended for IV and upwards) now at II and which I had not ordered to come on next day with the second party of porters (two parties A and B each of 20 had been formed for these purposes and B were a day behind us). The only plan was to make an early start next morning and get to II in time to forestall the departure of B party, I remember making this resolve in the middle of the night and getting up to pull my boots inside the tent from under the door; I put them inside the outer covering of my fleabag and near the middle of my body - but of course they remained frozen hard and I had a tussle to get them on in the morning. Luckily the sun strikes our tents early – 6.30 a.m. or little later at III and I was able to get off about 7.0. I left directions that half the men or as many less as possible should come ¼ of the way down and meet the men coming up so as to get the most important loads to III. I guessed that B party after a cold night would not start before 9.0 am and as I was anxious to find, if possible, a better way over the glacier I wasted some time in investigations and made an unsatisfactory new route, so that it was after 8.30 when I emerged from the trough; and a little further on I saw B party coming up. It was too late to turn them back. I found that they had some of them resolved that they would not be able to go to III and get back to II the same day and consequently increased their loads with blankets etc determining to sleep at III. This was the last thing I wanted. My chief idea at the moment was to get useful work out of B party without risking their morale or condition as I saw we were risking that of A. So after despatching a note to Noel at II I conducted B party slowly up the glacier. After making a convenient dump and sending down B party I got back to Camp III early afternoon, some what done and going very slowly at the last from want of food. In camp nothing doing. All porters said to be sick and none fit to carry a load. Irvine and Odell volunteered to go down to the dump and get up one or two things specially wanted – e.g. Primus stoves, which was done. The sun had left the camp sometime before they returned. A very little wall building was done this day notably round the N.C.O.’s tent otherwise nothing to improve matters. The temperature at p.m. (we hadn’t thermometers the previous night) was observed to be 2° F – 30 ° of frost an hour before sunset –; under these conditions it is only during the sunny windless hours that anything to speak of can be done; this day there were such hours but I gathered that sahibs as well as porters were suffering from altitude lassitude.

May 7 The night had been very cold -21 ½ ° i.e. 53 °of frost. Personally I had slept beautifully warmly and yet was not well in the morning. Odell and Irvine also seemed distinctly unfit. I decided to send Hazard down with some of A party to meet at the dump and bring up 10 of B (it had been arranged that this party were to come up again). Investigations again showed that no porters were fit to carry loads; several were too unwell to be kept up at III; not one had a spark of energy or seemed inclined to do a hand’s turn to help himself – the only live man in camp was our admirable Kami. I decided to send down the whole lot and to send up B next day to establish the camp and prove it habitable. While Hazard went off to meet B I collected the men at III. They had to be more or less pulled from their tents; an hour and a half must have been taken up in their getting a meal of tea and tsamfa which they must clearly have before going down; & much time too in digging out the sicker men who tried to hide away in their tents – one of them who was absolutely without a spark of life to help himself had swollen feet and we had to pull on his boots with our socks; he was almost incapable of walking; I supported him with my arm for some distance and then told off a porter to do that; eventually roped in three parties in charge of the N.C.O. I sent them off by themselves from the dump - where shortly afterwards I met Hazard. Four men of B had gone on to III but not to sleep. Three others whom we now proceeded to rope up and help with their loads alone consented to stay there.

A second day therefore passed with only 7 more loads got to III & nothing done to establish the camp in a more comfortable manner, unless it may be counted that this third night the six men would each have a high altitude sleeping bag: and meanwhile the morale of A partly had gone to blazes. It was clear to me that the morale of porters altogether must be restored if possible at once by bringing B partly up and giving them a day’s rest to make camp.

May 8. I made another early start and reached II at 9.0 am – and here met Norton and Somervill. By some mental aberration I had thought they would only reach II on this day – they had proceeded according to programme and come to II on the 7th. We discussed plans largely while I ate breakfast, in the mild, sheltered, sunny al fresco of II (by comparison). N. agreed with my ideas and we despatched all remaining B party to III with Somervell, to pick up their loads at the dump and carry them on. A had been filled up the previous night with hot food and were now lying in the sun looking more like men; the only question was whether in future to re establish the correct standard and make them carry all the way to III and back as was always done in 1922; I was strongly opposed to this idea, the best way of re establishing their morale I thought would be to give them a job well within their powers and if they improved as I hoped they might well carry loads the ¾ journey to the dump on 3 successive days - while B could ferry the last quarter once and twice on the two of the days when they would not be engaged in making camps: - this was agreed to more particularly by Geoffrey Bruce, who really runs the porters altogether, and who had now come up from I.

A day of great relief this with the responsibility shared or handed over; and much lying in the sun; and untroubled sleep at II.

May 9 I intended going ahead of the party to see how things were moving at III – for this day the camp was to be made wonderful. Seven men with special loads, fresh heroes from the Base were to go through to III the A men to return from the dump to II. As it turned out I escorted the first batch who were going through to III. The conditions when we emerged from the trough were anything but pleasant; under a grey sky the violent wind was blowing up the snow; at moments the black dots below me on the glacier all except the nearest were completely lost to view. The men were much inclined to put down their loads before reaching the dump and a good deal of driving had to be done. Eventually after waiting some time at the dump I joined Norton and Geoff and we escorted the last 3 loads for III the last bit of the way.

On such a day I didn’t expect III to be more congenial than it had been. However it was something to be greeted by the cheery noise of the Roarer Cooker; the R.C. is one of the great inventions of the expedition; we have two in point of fact one with a vertical and one with a horizontal flame – a sort of super Primus stove. Irvine and Odell had evidently been doing some useful work. It had been a triumph getting the R.C. to Camp III – it is an extravagant load weighing over 40lbs and it now proved to be even more extravagant of fuel than had been anticipated; moreover its burning was somewhat intermittent and as the cook even after instruction was still both frightened and incompetent when this formidable stove was not functioning quite sweetly and well a sahib had often to be called in to help. Nevertheless the R.C. succeeded in cooking food for the troops and however costly in paraffin oil that meal may have been it made the one great difference between Camp III as A party experienced it and Camp III now. Otherwise on this day set apart for the edification & beautification of this camp the single thing that had been done was the erection of one Mead tent to accommodate 2 more sahibs (only 2 more because Hazard came down this day). And no blame to anyone. B party was much as A party had been - in a state of oriental inertia; it is unfair perhaps to our porters to class then with Orientals in general, but they have this oriental quality that after a certain stage of physical discomfort or mental depression is reached they simply curl up. Our porters were just curled up inside their tents. And it must be admitted that the sahibs were most of the time in their tents no other place being tolerable. Personally I felt that the task of going round tents and seeing how the men were getting on and giving orders about the arrangements of the camp now naturally fell to Geoffrey Bruce, whose ‘pigeon’ it is to deal with porters. And so, presently, in my old place, with Somervell now as a companion instead of Hazard. I made myself comfortable; - i.e. I took off my boots and knickers, put on my footless stockings knitted for me by my wife for last expedition and covering the whole of my legs, a pair of grey flannel bags & 2 pairs of warm socks besides my cloth sided shoes & certain garments too for warming the upper parts, a comparatively simple matter. The final resort in these conditions of course is to put ones legs into a sleeping bag. Howard and I lay warmly enough and presently I proposed a game of picquette and we played cards for sometime until Norton & Geoff came to pay us a visit and discuss the situation. Someone a little later lied backer the flaps of the two tents facing each other so that after N & G had retired to their tent the other four of us began were inhabiting as it were one room and hopefully talked of the genius of Kami and the Roarer Cooker and supposed that a hot evening meal might sometime come our way. Meanwhile I produced The Spirit of Man and began reading one things and another – Howard reminded me that I was reproducing on the same spot a scene which occurred two years ago when he and I lay in a tent together. We all agreed that Kubla Khan was a good sort of poem. Irvine was rather poetry shy but seemed to be favourably impressed by the Epitaph to Grey’s Elegy. Odell was much inclined to be interested and liked the last lines of Prometheus Unbound. S, who knows quite a lot of English Literature had never read a poem of Emily Bronte’s and was happily introduced. And suddenly hot soup arrived.

The following night was one of the most disagreeable I remember. The wind came in tremendous gusts and in spite of precautions to keep it out the fresh snow drifted in; if one’s head was not under the bed clothes one’s face was cooled by the fine cold powder and [May 10 written in margin] in the morning I found about 2 ins of snow all along my side of the tent. It was impossible to guess how much snow had fallen during the night when first one looked out. The only certain thing was the vile appearance of thing’s at present. In a calm interval one could take stock of a camp now covered in snow - and then would come the violent wind and all would be covered in the spindrift. Presently Norton and Geoff came into our tent for a pow pow. G. speaking from the porters’ point of view was in favour of beating a retreat. We were all agreed that we must not risk destroying the morale of the porters and also that for two or three days no progress could be made towards the North Col. But it seemed to me that in a normal course of events the weather should now re-establish itself and might even be sufficiently calm to get something done this afternoon; and that for the porters the best thing of all would be to weather the storm up at III. In any case it would be early enough to decide for a retreat next day. These arguments commended themselves to Norton; and so it was agreed. Meanwhile one of the most serious features of the situation was the consumption of fuel. A box of meta and none could say how much paraffin (not much however) had been burnt at II; here at III no water had yet appeared and snow must be melted for everyone at every meal – a box of Meta had been consumed here too and Primus stoves had been used before Roarer had made its appearance yesterday. Goodness knew how much oil it had used. It was clear that the first economy must be in the number (6) of sahibs at III. We planned that Somervill, Norton and Odell should have the first whack at the North Col and Irvine and I finish the good work next day – Irvine and I therefore must go down first. On the way down Irvine suffered very much and I somewhat for the complaint known as glacier lassitude – mysterious complaint, but I’m pretty certain that in his case the sun and the dazzling light reflected from the new snow had something to do with the trouble.

A peaceful time at II with Beetham and Noel.

May 11. The weather hazy and unsettled looking.

I despatched 15 loads up to the dump and arranged for the evacuation of two sick men – of whom one had very badly frost bitten feet apparently a Lepcha unfit for this game and the other was Sangha, Kellas’s old servant who has been attached to Noel this expedition and last, a most valuable man who seemed extremely ill with bronchitis. The parties had been gone half an hour before we were aroused by a shout and learnt that a porter had broken his leg on the glacier. We quickly gathered ourselves into a competent help party and had barely started out when a man turned up bearing a note from Norton – to tell me as I half expected that he had decided to evacuate III for the present and retire all ranks to the B.C.

The wounded man turned out to be nearer at hand and not so badly wounded (a bone broken in the region of the knee) as I had feared.

This same evening Beetham, Noel, Irvine, and I were back at the B.C., the rest coming in next day.

Well, that’s the bare story of the reverse, so far as it goes. I’m convinced Norton has been perfectly right. We pushed things far enough. Everything depends on the porters and we must contrive to bring them to the starting point – i.e. 3 at the top of their form. I expect we were working all the time in ‘22 with a smaller margin than we knew - it certainly amazed me that the whole ‘bandobast’ so far as porters were concerned worked so smoothly. Anyway this time the conditions at III were much more severe and not only were temperatures lower, but wind was more continuous and more violent. I expect these porters will do as well in the end as last time’s. Personally I felt as though I were going through a real hard time in a way I never did in ’22. Meanwhile our retreat has meant a big waste of time. We have waited down here for the weather & at last it looks more settled and we are on the point of starting up again. But the day for the summit is put off from the 17th to the 28th; and the great question is will the monsoon give us time?

May 16. That is all very impersonal but I wanted to get the story down. You’ll be glad to hear that I came through the bad time unscathed indeed, excellently fit. I must tell you that with immense physical pride I look upon myself as the strongest of the lot the most likely to get to the top with or without gas. I may be wrong but I’m pretty sure Norton thinks the same. He and I were agreeing yesterday that none of the new members, with the possible exception of Irvine can touch the veterans and that the old gang are bearing everything on their shoulders and will continue to do so forcement. The performance of Odell and Hazard on the day they were supposed to reconnoitre the North Col was certainly disappointing. And Beetham has not recovered his form. None of these three has shown that he has any real guts; it is an effort to pull oneself together and do what is required high up, but it is the power to keep the show going when you don’t feel energetic that will enable us to win through if anything does. Irvine has much more of the winning spirit - he has been wonderfully hard working and brilliantly skilful about the oxygen; against him is his youth (though it is very much for him some ways) – hard things seem to hit him a bit harder – and his lack of mountaineering training and practice, which must tells to some extent when it comes to climbing rocks or even to saving energy on the easiest ground. However he’ll be an ideal campaigning companion and with as stout a heart as you could wish to find; - if each of us keeps up his strength as it is at present we should go well together.

Somervell seems to me a bit below his form of two years ago and Norton is not particularly strong I fancy, at the moment; still they’re sure to turn up a pretty tough pair. I hope to carry all through now with a great bound now. We have learnt from experience and will be well organised at the camps. Howard and I will be making the way to Chang La again – 4 days hence and eight days later – who can tell? Perhaps we shall go to the top on Ascension Day May 29.

I don’t forget meanwhile that there’s the old monsoon to be reckoned with, and a hundred possible slips between the B.C. and the summit. I feel strong for the battle but I know every ounce of strength will be wanted.

I must get off a little letter to each of the girls by this mail. I wish I had time to present to your mind a few of the amazing scenes connected with this story. As it is it is dull I fear – but perhaps not to you. My love to people in Cambridge, David and Claud and Jim especially and kind remembrances to Cranage and Mrs Cr. I wonder what you’ll be doing about putting people up during the Summer Meeting.

Great love to you always, dearest Ruth. Your loving George

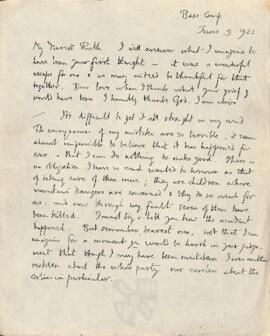

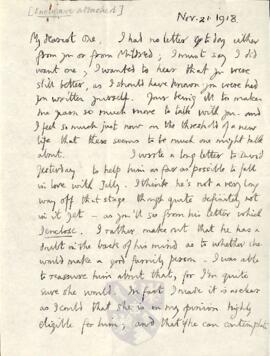

![Letter from George to Ruth Mallory, 26 May 1922 [first attempts to summit with and without oxygen]](/uploads/r/null/e/7/1/e713aa9025b80ad036db2212b403029949e0050e1f7d581c5ca4250b5afdcd7e/PP_GM_3_1_1922_15_watermark_142.jpg)