Autograph letter addressed from "Berkeley Square", signed, to Jean Sylvain Van de Weyer, enquiring about wine merchants and inviting him to stay in the country.

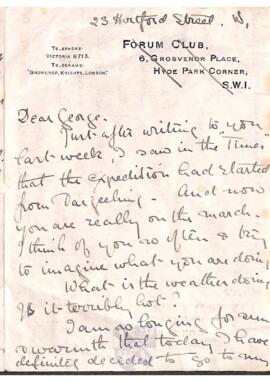

Van de Weyer, Jean Sylvain (1802-1874), diplomatLetter from Stella, believed to be Stella Cobden-Sanderson. Postmarked 2 April. Mallory used the envelope to note down the code numbers and pressures of five oxygen cylinders.

This letter was found on George Mallory's body in 1999. It was wrapped in a handkerchief along with two other letters.

Full Transcript

Forum Club,

6, Grosvenor Place,

Hyde Park Corner,

S.W.I.

[Address has been crossed out and replaced with ’23 Hertford Street. W,]

Dear George,

Just after writing to you last week, I saw in The Times that the expedition had started from Darjeeling – And now you are really on the march. I think of you so often & try to imagine what you are doing. What is the weather doing? Is it terribly hot?

I am so longing for sun & warmth that today I have definitely decided to go to my friends near Cannes for about a month from the middle of May – It won't be fashionable but a great great joy to get to the south. The flowers will be heavenly then.

My alternative was to do a round of visits in England. For a long time I was tempted to do this because I love my friends & making new ones. But I suddenly had such a desire for the south & peace. And now I am glad to have decided this.

I expect to go to Paris for Easter with the Macmillans then join the Shears & other American friends in Paris until middle of May. So I shall start with a gay time.

Last night I saw Shaws St Joan” I was very much moved & impressed with it. And I do think that its wonderful of Shaw at his age to write without exaggerating his mannerisms. Some of the dialogues are far too long – But its wonderfully written & without the desire to show his own personality too much. The acting is excellent & its most beautiful to look upon.

I had lunch with Mrss Graies yesterday at her club – Sissie is in Italy & she pressed me to go saying she was lonely & had a great many things she wanted to discuss with me. But these consisted of abuse of Macdonald because she had not seen him, that Ishbel's head had been turned, & that Macdonald had treated Sissie badly. In between this, improper stories. And all this shouted at the top of her voice in a public room. My answers having to be made equally loud down a speaking tube! Poor Sissie, I am really sorry for her.

London with the strikes has been very exhausting & terrible for the wretched daily workers. It’s amazing how good natured is an English crowd.

On Saturday the day of the boat race my brother is expecting nearly 200 as their garden goes down to the river at Hammersmith. Mother & I are not going as we have too many old associations of my father.

I am longing to hear from you since your arrival.

My love to you dear

Your affectionate

Stella

April 2

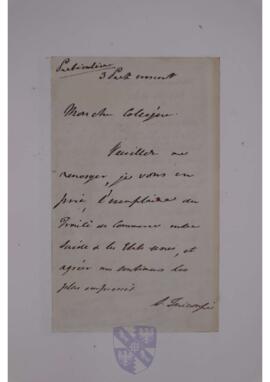

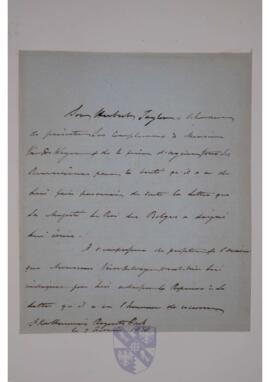

Autograph letter in French, addressed from "3 Park Crescent", signed, to Jean-Sylvain Van de Weyer.

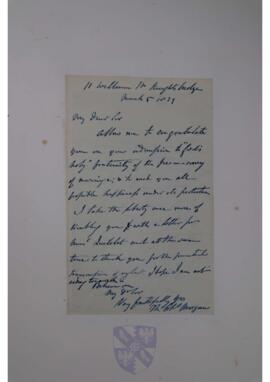

Van de Weyer, Jean Sylvain (1802-1874), diplomatAutograph letter addressed from "11 William Street, Knightsbridge", signed, to Jean-Sylvain Van de Weyer, congratulating him on his admission into the Freemasons.

Van de Weyer, Jean Sylvain (1802-1874), diplomatAutograph letter addressed from "2 Eccleston Street", signed, to Jean-Sylvain Van de Weyer, inviting him to a dinner in honour of Sir John Herschel, promising that if he does attend he would be sat near Herschel and the president of the Royal Society.

Van de Weyer, Jean Sylvain (1802-1874), diplomatAutograph letter addressed from "Melbourne Lodge, Claremont", signed, to Jean-Sylvain Van de Weyer.

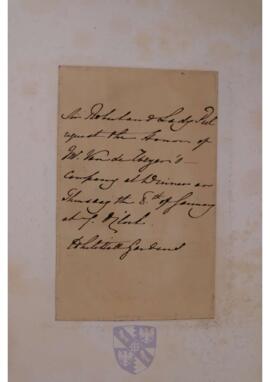

Van de Weyer, Jean Sylvain (1802-1874), diplomatAutograph letter, to Jean Sylvain Van de Weyer, requesting his company at dinner on Thursday 8th January.

Van de Weyer, Jean Sylvain (1802-1874), diplomatAutograph letter addressed from "Whitehall", signed “Robert Peel”.

Transcription of opening lines: “Gentleman, I am very much afraid, that amid the occupations in which I have been engaged since my return to England, I omitted properly to acknowledge your kind and effective attention to a Request made to you by my friend, Henry Baring […]”.

Autograph letter addressed from "Chesterfield Street", signed, to Jean Sylvain Van de Weyer regarding his sending an engraving to the recipient of the letter.

Van de Weyer, Jean Sylvain (1802-1874), diplomatTranscription of opening lines: “I have the pleasure to acquaint you that at a meeting of the Royal Academicians Club held on the 7th [?] you were elected a member”. Westmacott offers his congratulations on the occasion.

Van de Weyer, Jean Sylvain (1802-1874), diplomatAutograph letter in French, addressed from "Cavendish Square", signed, to Jean Sylvain Van de Weyer, enclosing his portrait and desiring to arrange a visit.

Van de Weyer, Jean Sylvain (1802-1874), diplomatAutograph letter, signed, to Jean Sylvain Van de Weyer regarding a trip to Constantinople.

Van de Weyer, Jean Sylvain (1802-1874), diplomatAutograph letter addressed from "41 Upper Grosvenor Street", signed, to Jean-Sylvain Van de Weyer concerning business exchanges and transactions.

Van de Weyer, Jean Sylvain (1802-1874), diplomatAutograph letter addressed from "Ordnance Office", to Jean-Sylvain Van de Weyer, presenting his compliments and enclosing a letter from the Duke of Sussex.

Van de Weyer, Jean Sylvain (1802-1874), diplomatAutograph letter addressed from "Rodney Street", signed, to Francis Boott. The letter also has MS annotations added by Boott including the date of receipt (30th August 1818).

Transcription of opening lines : “My dear Sir, I return you the crown of the Pine immediately for fear of injury by delay.”

Boott’s letter in reply is in the Linnean Society Archives, reference GB-110/JES/COR/20/118.

Autograph letter, signed, to the Secretary of the Artists’ Benevolent Institution. Davy is unable to accept the invitation of the Steward to dine with the members of the Institution on Friday 5th May and therefore returns his dining card. Begs that the Secretary will pass on his regrets and communicate his thanks for the invitation.

Van de Weyer, Jean Sylvain (1802-1874), diplomatAutograph letter in French, addressed from "St Katherine’s Regents Park", to Jean-Sylvain Van de Weyer.

Van de Weyer, Jean Sylvain (1802-1874), diplomatTyped letter from Sir Henry Willink to Professor Basil Willey about the offer to C.S. Lewis of the chair of Medieval and Renaissance English.

Thanks him for his letter and he too had heard from Tolkien.

He had also received an embarrassed letter from C.S. Lewis.

He would tell him another invitation to accept the post had been sent out to their second choice and nothing could be done until it had been answered. Was making enquiries of the Registrary and Secretary General as to the extent to which Lewis's terms could be discussed in the event of Miss Gardner's refusal.

Typed letter from Sir Henry Willink to J.R.R. Tolkien about the offer to C.S. Lewis of the chair of Medieval and Renaissance English.

Before getting his letter he had received two from Lewis refusing the offer of the chair. After consultation with Prof. Willey he had invited their second choice to accept the position and they could do nothing until they had heard back from Miss Gardner. In the meantime he had been writing to Lewis to keep the case open in case he was in a position to offer it again.

Typed copy letter from Sir Henry Willink to C.S. Lewis.

The news of his acceptance of the chair of Medieval and Renaissance English was now known.

Suggests a form of words Lewis could use in reply to offers of rooms and a Fellowship from other Colleges [Willink was Vice-Chancellor of the University as well as Master of Magdalene and so had prior knowledge of the appointment and had the advantage in being the first to be able offer Lewis a Fellowship at Magdalene]. Makes it clear he was free to accept an offer from another College if he would like.

Typed copy letter from Henry Willink to C.S. Lewis.

Writing in his capacity as Master of Magdalene College he offers Lewis a Fellowship and rooms at Magdalene and hopes that he won't be accused by other Colleges of using his prior news of the appointment to the chair of Medieval and Renaissance English as he was also the Vice-Chancellor. Explains the rules about quotas of Professorships at the Colleges and thinks that there will be two or three other Colleges in a position to offer him rooms but hopes he will accept Magdalene.

Typed copy letter from Sir Henry Willink to C.S. Lewis.

Lewis's letter of 4 June had given him news [acceptance of the Chair of Medieval and Renaissance English] which when published would give immense pleasure in Cambridge.

Discusses possible start dates for the tenure.

Typed copy letter from Sir Henry Willink to C.S. Lewis.

Their second choice for the Chair of Medieval and Renaissance English had declined and hopes that he will now accept the invitation.

Suggests a date of 1 October as a possible start date for the tenure but if he was still unsure he suggests meeting to discuss outstanding issues.

Hopes that he will approach the Master of Magdalene [Lewis's sister College] enquiring about living at that College before accepting any other invitations he would receive [Willink was Master of Magdalene as well as Vice-Chancellor of the University in which capacity he was writing about the offer of the chair].

Typed copy letter from Sir Henry Willink to C.S. Lewis.

Thought that his letter was such a definite refusal of the Chair of Medieval and Renaissance English, that after consultation with Prof. Willey he had sent an invitation to their second choice and would have to wait for a reply.

Clarifies the residency rules and how long a Professor could be absent. Chairs at Cambridge were not tied to a particular College and thought that suitable rooms and a Fellowship could be easily found for him.

If Choice No. 2 refuses then he thinks they should meet to talk it over. Regrets that he sent the letter to Choice No. 2.

Typed copy letter from Sir Henry Willink to C.S. Lewis.

Is writing after the College meeting as promised. They greatly hoped he would accept their invitation to live at Magdalene. It was their unanimous intention to elect him to a Professorial Fellowship as soon as possible under the University Statutes. Couldn't forecast when this would be.

In the interim their offer would include all the social rights of a Fellow - dining in Hall etc but he would not have to attend College meetings or be entitled to the Fellow's allowance of 3s 0d a day during residence. They could offer an attractive set of rooms in First Court - two sitting rooms and a bedroom and bathroom.

Hoped he would accept presentation by the College for a degree by incorporation in due course.

Hoped he would accept their offer even though it fell short of the immediate offer of a Fellowship which Christ's and Downing were in a position to make.

Suggests dates in the summer for a meeting to discuss various things and settle details about his rooms.

Typed copy letter from Sir Henry Willink to C.S. Lewis.

Was delighted that Lewis accepted their offer of a Fellowship and rooms at Magdalene.

Understands about the difficulty of him coming to Cambridge in the near future, he would just like to start their acquaintance and make sure his rooms were as he liked them.

[handwritten note by Willink at the bottom of the page]:

"C.S. Lewis came into residence in October 1954 and was elected to a Professorial Fellowship on 18 January 1955".

Typed copy letter from Sir Henry Willink to C.S. Lewis.

Transcript

Thank you so much for your second letter.

But I am sorry to have given you the burden of writing a second time. It is abundantly clear that you have cogent reasons for not making the move which we had so much hoped would be possible.

Typed copy letter from Sir Henry Willink to C.S. Lewis.

The 'time for consultation' to which he referred in his letter of 8 June had begun and would run until 24 June when they would have a College meeting. He would write immediately after the meeting.

Returns his letter from Corpus Christi.

Apologises for the brief note as he was just off to London.

Typed copy letter from Sir Henry Willink to C.S. Lewis.

Thanks him for his letter of 12 May and the kind things he said about the invitation to become the first Professor of Medieval and Renaissance English.

Expresses the wish of many in Cambridge that he should come and live in Cambridge. Thinks that he will receive several personal letters from people who he knows who will be more persuasive. Hopes he will reconsider and withdraw his refusal.

He did not feel the need to write to their second choice before 1 June.

Typed copy letter from Sir Henry Willink to C.S. Lewis.

Asks if he could reply to his letter of 24 June so that he could report back at the next College meeting and confirm his acceptance of their offer. The Master of Corpus had telephoned hi to say that as he [Lewis] had accepted rooms at Magdalene they would abandon their attempts to entice him to the Society.