Brief Summary

Reconnaissance to find a route to the North Col and therefore a route to the summit of Everest.

Detailed Summary

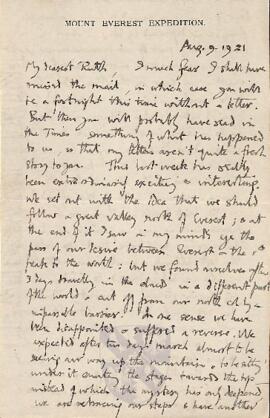

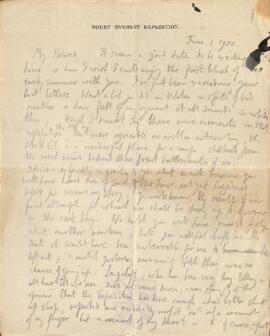

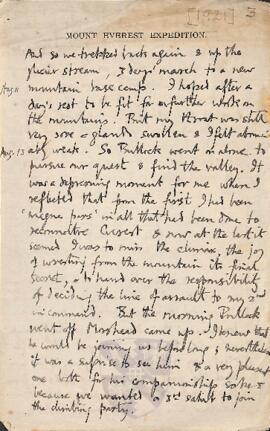

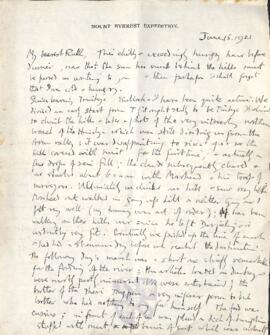

On the first page Mallory gives a very brief summary of events on each day.

2 August – Elaborate preparations to leave Kharta. Took same mountaineering stores as they had from Tingri but left behind the primus stoves and a bundle of sleeping sacks. Thought they were in easy reach of the base of Kharta and could send for them later. Main problem was rations. Porters had decided they didn’t have enough to eat. Howard-Bury had accused Gyaltzen of making money out of them. Needed to devise a way of providing rations so Gyaltzen was not involved buying them. It was decided he would buy food on credit during the march and the Colonel would pay later.

It was a hazardous adventure but the prospects seemed rosy. The great glacier stream joining the Arun just below them was presumed to come from Everest and the left branch from the North Col. They expected to be on the North Col within a few days. However, the start from Kharta was dilatory. The Sidar was up late and hadn’t organised anything. The loads had been counted wrong, they had no animals and had to leave three loads behind. In Shikar Kharta [Kharta Shekar] they were received by the Dzongpen [governor] and had tea and biscuits. There was an argument with the porters about rations and they had to be urged to continue. They stopped at a house to drink and admire the rugs that were being woven. Then they came to a monastery where one porter refused to continue on. The porter put up the tents at the junction of the valley after only ½ days march.

3 August – As they had stopped after so short a march the day before they had a long march on the second day. They had a rise of 4,000 ft to the pass. They pitched tents on a yak grazing ground above the valley. Flowers very good on both sides the pass and he found the blue primula. No sheep or goats.

4 August – Clouds had not lifted and they had a descent of 800 ft to river bed. There was rich vegetation which he describes. Heavy rain cam e down and they decided to set up camp although it was early. Thought they were going in the wrong direction and wanted clouds to clear to make sure. Discussion with Headman and was assured a route did exist up the valley

5 August – Clouds began to clear so they could see Everest. Reconnaissance out from the camp and up a final low peak showed no easy way existed which could take them round to the end of East ridge.

6 August - Fine morning and pleasant walk up the right bank of the glacier. Fine show of gentians. A steep rise of about 800 ft lead to a very small lake where we camped. Snow fell almost continuously in afternoon and evening. Clouds broke to give a wonderful view at sunset.

7 August – Later start than planned. Cook was ill and everything was covered with snow but they got off at 4.10am. Their objective was the conspicuous sharp show peak, third from the N.E. Arete of Everest. Describes the trek to the col which they reached at 8.45am. Had a hearty meal and took two photos. Not possible to see the head of the glacier north of them. They climbed up and it was clear that the glacier head was a snow col. He insisted that the peak ahead must be climbed in order to try and see the north col. The next section was very steep. The east face in front of them had to be avoided. The south face was separated from them by a broad gully. Snow was very deep and he was constantly thinking of the danger of avalanches. They managed to get onto the steep south slope. The porters (Nimya, [Nyima] Alugga, Pema, and Dasno) learnt much about using the rope. They reached the far edge at 12:15 pm and looked across directly to the east ridge of Everest although still couldn’t see the North col. The party lay down to sleep while he took photos and ate some food before trekking the final slopes. He then went on with Nimya [Nyima] and Dasno. They abandoned their snowshoes at the foot of a very steep snow face. Dasno then abandoned them. As he thought the snow was in too bad a condition. It was a place to fear an avalanche. It was exhausting and he disn’t get a clear view as a reward. Bullock led down, very slow in the steep snow. He had a baddish headache by this time and felt unwell. When they got back at about 4.30pm he felt exhausted and feverish and in spite of warm clothes couldn’t prevent himself shivering.

8 August – Porters were delayed in arriving so they prepared to move without them. He felt weak walking. Met up with porters and heard Howard-Bury had arrived at Base Camp. Reached Base Camp at 11.15am. Howard-Bury was out photographing. He went to bed. Discussed rations again and decided to give the porters a share of the balance and they were happy.

9 August - Felt slack with swollen glands in the neck and a sore throat but was fitter to walk. Collected flowers and seeds on the way down. Howard-Bury decided to go back to Kharta by another pass. Had to stand and wait ½ hour for the clouds to thin so he could take 2 photographs of the summit. He saw a beautifu lblue gentian which he had never seen before in the Alps. He realised he wasn’t carrying his woollen waistcoat. Retraced his steps but couldn’t find it. Offered a reward to any porter who could find it. They looked but couldn’t see it.

10 August – Saw a tiny yellow saxifrage which Wollaston hadn’t got. Continued down hill and was pleased he could leave Bullock behind going downhill as well as up. The meadows in the valley were delicious and very warm.

11 August - Bathed in the stream. Had been promised yakmen were coming but they didn’t arrive. Managed to get hold of two yaks and left packs for porters to bring. He felt unwell and the porters were slack. Gorang lied by saying there was no water higher up. Had to persuade the porters to continue. Found water and a good sheltered spot for the camp.

12 August: A days rest and fuel collecting. He kept to his bed.

13 August - feeling feeble with a sore throat and swollen glands. Morshead arrived with a note from Wollaston and Bury which cheered him a good deal. Bullock sent a note in the evening with depressing news that the valley was ‘no good’. This mean fresh efforts of reconnaissance. Was a comfort to have Morshead.

14 August – they searched for a possible approach and had been mistaken about the topography of the expected valley. Hoped two more days would settle the question.

15 August – He and Morshead followed a shelf but found no exit to their glacier and had to stop, camping at a place with just enough room where the ground was not too sloping to pitch the three tents.

16 August - Best chance of a clear view was to go up. Doesn’t know why he went one except he was so miserable he wanted to reduce the rest of the party to a like state of mind. Bullock lead down the glacier badly doing little to avoid the crevasses which were covered by snow. They discussed plans at some length. A sketch map had arrived from Wheeler the day before showing a glacier [East Rongbuk Glacier] of enormous dimensions running north from Everest and draining into the Rongbuk valley but it’s inaccuracies had made them discount Wheler’s conclusion too much. He showed no East ridge to the North Peak. He thought wheeler had mistaken that ridge for the N.E. Arete of Everest (which he showed S.E.). He had little hope it would be of service to them. It could only be so if it drained on to the Rongbuk valley as Bullock thought probable. Either Wheeler must be right or the North Col was lower than they thought and the cwm high enough to push its glacier near it. They agreed he would descend to the north to see if there was a glacier in that direction.

17 August Gives three causes of the failure of rations supply.

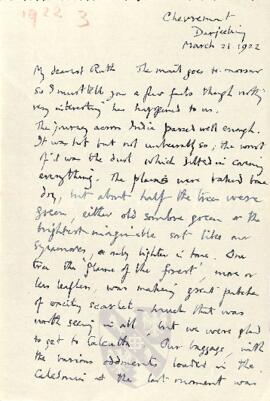

![Diary Entries, 2-17 August 1921 [discovery of North Col]](/uploads/r/null/b/8/b/b8bd3cb0b585515bb92a05d9f965942ab7b49fafbeffbfca40c9525687a07fc2/PP_GM_3_1_1921_26_watermark_142.jpg)

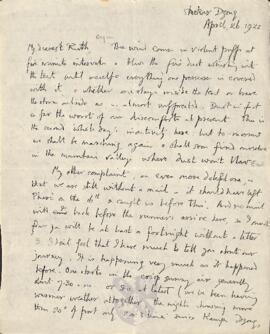

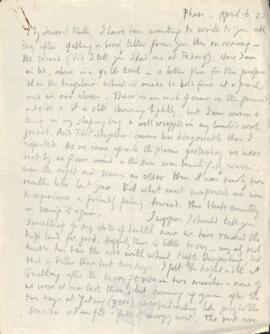

![Letter from George to Ruth Mallory, 22 August 1921 [confirms North Col route to summit]](/uploads/r/null/7/9/4/7947af1191c9f283fdaf014a03d53fc583935670c12d39256ab6598f5573a2b4/PP_GM_3_1_1921_28_watermark_142.jpg)

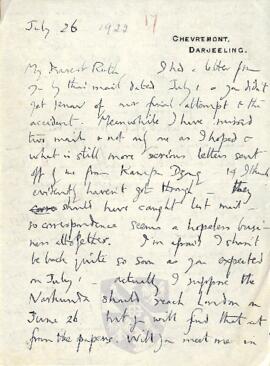

![Letter from George to Ruth Mallory, 26 May 1922 [first attempts to summit with and without oxygen]](/uploads/r/null/e/7/1/e713aa9025b80ad036db2212b403029949e0050e1f7d581c5ca4250b5afdcd7e/PP_GM_3_1_1922_15_watermark_142.jpg)

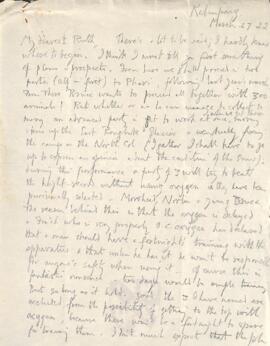

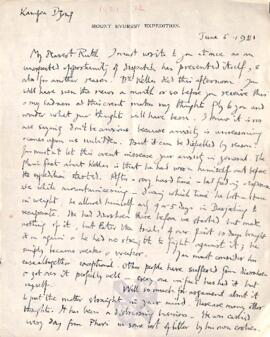

![Letter from George to Ruth Mallory, 8 June 1921 [first view of Mount Everest]](/uploads/r/null/b/0/8/b087a6ea8237585813251e913c908f81472ae581e133913d6193b97243ecb09c/PP_GM_3_1_1921_14_watermark_142.jpg)