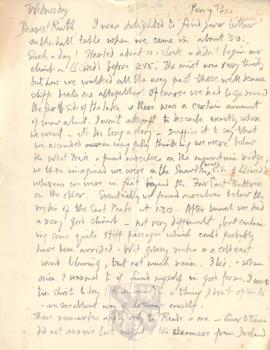

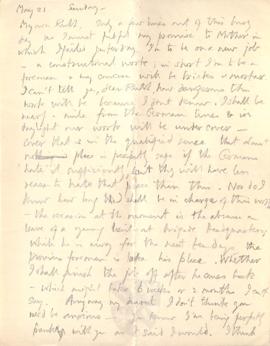

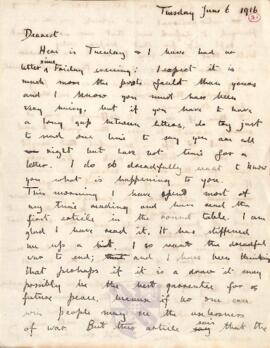

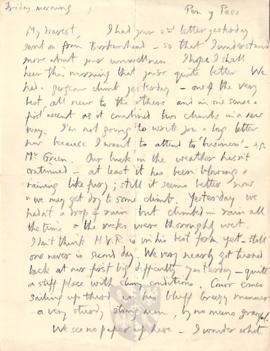

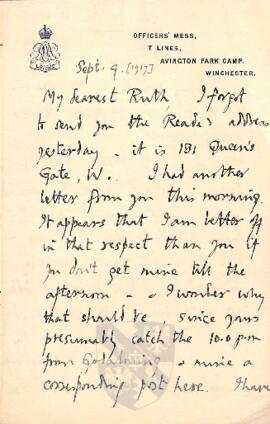

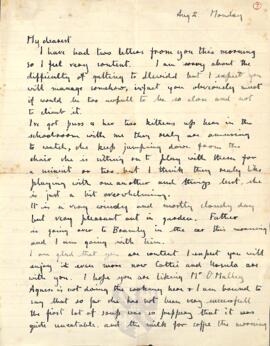

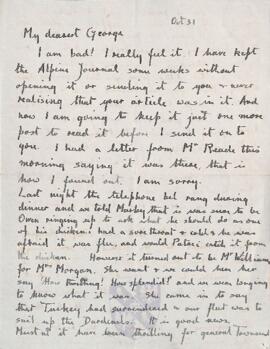

Letter to Ruth Mallory describing the Avalanche in which 7 porters were killed.

Full Transcript

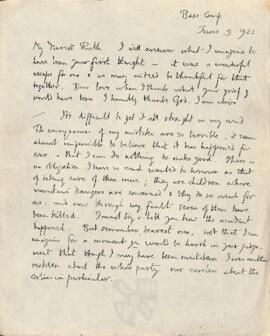

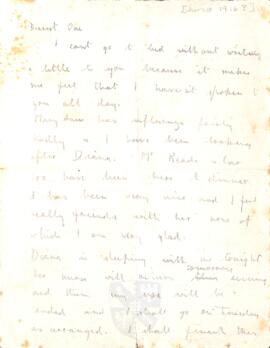

My dearest Ruth, I will answer what I imagine to be your first thought - it was a wonderful escape for me & we may indeed be thankful for that together. Dear love when I think what your grief would have been I humbly thank God I am alive.

/ It’s difficult to get it all straight in my mind. The consequences of my mistake are so terrible; it seems almost impossible to believe that it has happened for ever & that I can do nothing to make good. There is no obligation I have so much wanted to honour as that of taking care of these men; they are children where mountain dangers are concerned & they do so much for us; and now through my fault seven of them have been killed. I must try to tell you how the accident happened. But remember dearest one, not that I can imagine for a moment you would be harsh in your judgement that though I may have been mistaken I was neither reckless about the whole party nor careless about the coolies in particular.

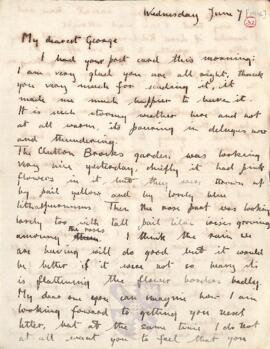

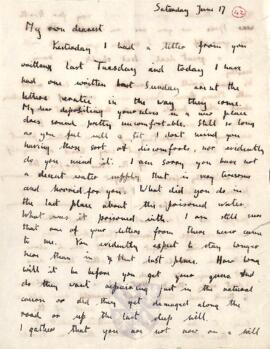

When we started from the Base Camp on June 3 the clouds were thickening & it was evident that very soon the monsoon would be upon us; but none can say how soon in such circumstances the monsoon will make climbing impossible. I walked up half despondently with Finch to No 1 Camp; he was clearly quite unfit & could barely reach the camp. Next morning he went back to the Base leaving Somervell & me for the high climbing with Wakefield and Crawford to be back us up.

During the night of the 3rd snow fell heavily & continued on the 4th. We spent a cold day in the poor shelter at Camp 1, a little hut with walls about 3 ft 6 in high built of the stones that lay about there & roofed with the outer fly of Whymper tent. The white snow dust blew in through the chink & one wondered naturally, Isn’t it mere foolishness to be attempting Everest now that the snow has come? It was clear that if we were to give up the attempt at once no one would have a word to say against our decision. But it seemed to me too early to turn back & too easy - we should not be satisfied afterwards. It would not be unreasonable to expect a spell of fair weather after the first snow as there was last year; this might give us our chance at last, a calm day in the balance between the prevailing west wind & the south east monsoon current. And if we were to fail how much better I thought to be turned back by a definite danger or difficulty on the mountain itself.

On the 5th will too [many crossed through] much cloud still hanging about the glacier we went up in one long march to Camp 3 - a wet walk in the melting snow & with some snow falling. At the camp not less than a foot of snow covered everything. The tents which had been struck but not packed up contained a mixture of ice, snow, & water; more than one was badly rent in putting it up. The prospects were not very hopeful.

There was no question of doing anything on the 6th, the best we asked for was a warm day’s rest. We had a clear day of brilliant sunshine, the warmest by far that any of us remembered at camp 3. The snow solidified with amazing rapidity; the rocks began to appear about our camp; and though the side of Everest facing us looked cold & white we had the satisfaction of observing during the greater part of the day a cloud of snow blown from the North Ridge. It would not be long at that rate before it was fit to climb.

The heavy snow of the 4th & 5th affected our plans in two ways. As we should have to expect heavier work high up we should have hardly a chance of reaching the top without oxygen, & in spite of Finch’s absence with his expert knowledge we decided to carry up ten cylinders with the two apparatus used by Finch and G. Bruce to our old camp established on the first attempt at 25,000 ft; so far we should go without oxygen; in taking up the camp (one of the 2 Mummery tents & the sleeping sacks) another 1000 ft we might find it advisable to use each one cylinder; in any case we should have 4 cylinders each to carry on with us next day.

Our chief anxiety was to provide for the safety of the [‘coolies’ crossed out] porters. We hoped the conditions might be good enough to send them down by themselves to the North Col; & it was arranged that Crawford should meet them at the foot of the ridge to conduct them properly roped over the crevasses to Camp 4; there they would remain until we came back from the higher camp & all would go down together. Crawford was also to arrange for the conduct of certain superfluous porters who were to come up to Camp 4 but not stay there across the steep slope below the camp, the one place which in the new conditions might prove dangerous. With these plans we thought we might move up from Camp IV on the 4th day of fine weather should the weather hold, & still bring down the party safely whatever the monsoon might do. A change of weather was to be feared sooner or later, but we were confident we could descend the North Ridge from our high camp in bad weather if necessary, & three of us, or if Wakefield came up, four, would then be available to shepherd the coolies down from the North Col.

But the North Col has first to be reached. With the new snow to contend with we should have hard work; perhaps it would take us more than one day; the steep final slope might be dangerous; we should perhaps find it prudent to leave our loads below it & come up easily enough in our frozen tracks another day.

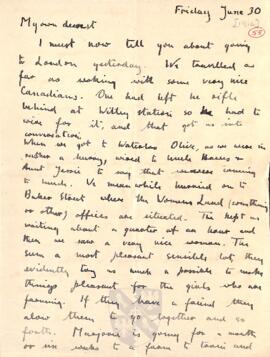

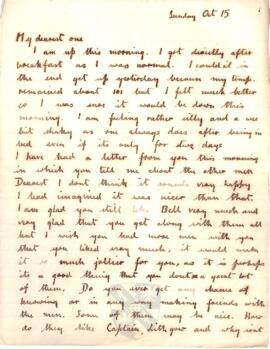

We set out from Camp 3, Somervell Crawford, & I with 14 porters at 8 a.m. on the 7th. A party including four of the strongest porters were selected to lead the way over the glacier. They did splendid work trudging the snow with loads on their backs; but it took us two hours to the foot of the great snow wall & it was 10.15 a.m. when Somervell, I, one porter, & Crawford, roped up in that order, began the ascent. We found no traces at first of our previous tracks, & were soon crossing a steep ice slope covered with snow. It was remarkable that the snow adhered so well to this slope, where we had found bare ice before, that we were able to get up without cutting steps. In this harmless place we had tested the snow & were more than satisfied.

Higher up the angle eases off & we had formally walked up at comparatively gently angels in the old snow until it was necessary to cross the final step slope below Camp 4.

Now we had to content with snow up to our knees. Crawford relieved Somervell & then I took a turn. About 1.30 p.m. I halted & the porters following in three parties came up with us. Somervell who was the least tired among us now went ahead continuing in our old line & still on gentle slopes about 200 ft below some blocks of fallen ice which mark the final traverse to the left over steeper ground. I was following up in the steps last on our rope of four when at 1.50, I heard a noise not unlike an explosion of untamped gunpowder. I had never before been [knew crossed out] near an avalanche of snow: but I knew the meaning of that noise as though I were accustomed to hear it every day. In a moment I observed the snow’s surface broken only a few yards away to the right & instinctively moved in that direction. And then I was moving downward. Somehow I managed to turn out from the slope so as to avoid being pushed headlong & backwards down it. For the briefest moment my chances seemed good as I went quietly sliding down, with the snow, Then the rope at my waist tightened & held me back. A wave of snow came over me. I supposed that the matter was settled. However I thrust out my arms to keep them above the snow & at the same time tried to raise by back, with the result that when after a few seconds the motion stopped I felt little pressure from the snow & found myself on the surface.

The rope was still tight about my waist & I imagined that the porter tied on next one must be deeply buried; but he quickly emerged near me no worse off than myself. Somervell & Crawford too were quite close to me & soon extricated themselves, apparently their experiences were much the same as mine. And where were the [rest crossed through] porters, we asked? Looking down over the broken snow we saw one group some distance below us. Presumably the rest must be buried somewhere between us & them. No sign of them appeared; and those we saw turned out to be the group who had been immediately behind us. Somehow they must have been caught in a more rapid stream & carried down a hundred feet further than us. They pointed below them; the others were down there.

It became only too plain as we hurried down that the men we saw were standing only a little way above a formidable drop. The others had been carried over. We found the ice cliff to be from 40 ft to 60 ft high, the crevasse below it was filled up with the avalanche snow & these signs enough to show us that the two missing parties of four & five were buried under it. From the first we entertained little hope of saving them. The fall alone must have killed the majority, & such proved to be the case as we dug out the bodies. Two men were rescued alive & were subsequently found to have sustained no severe injuries; the remaining seven lost their lives /.

There is the narrative - the bare facts, on separate sheets for your convenience - not my letter to you but a more impersonal account explaining our plans & their fatal conclusion. I hope it will suffice to let you understand what we were about. You may read between the lines how anxious I was about the venture. S. [Somervell] & I knew enough about Mount Everest not to treat so formidable a mountain contemptuously. But it was not a desperate game, I thought, with the plans we made. Perhaps with the habit of dealing with certain kinds of danger one becomes accustomed to measuring some that are best left unmeasured & untried. But in the end I come back to my ignorance; one generalises from too few observations & what a lifetime it requires to know all about it! I suppose if we had known a little more about conditions of snow here we should not have tried those slopes – [but crossed through] and not knowing we supposed too much from the only experience we had. The three of us were deceived; there wasn’t an inkling of danger among us. //

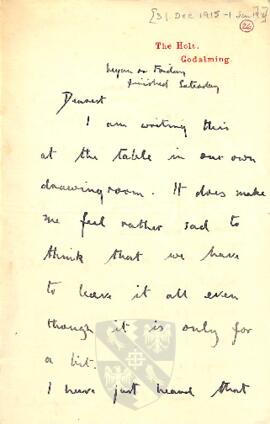

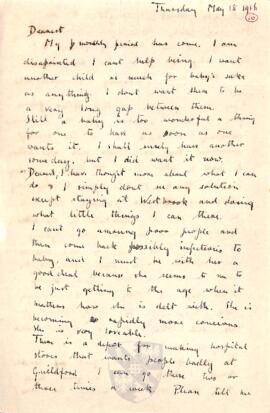

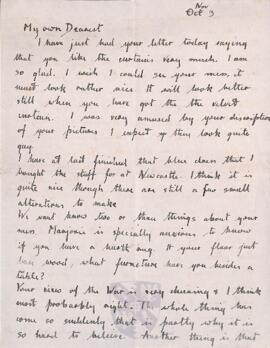

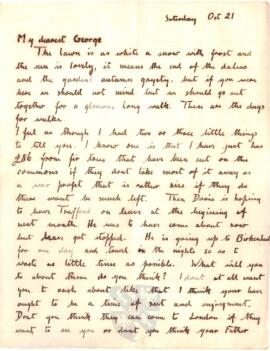

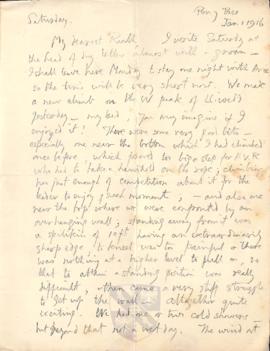

Writes again on ‘June 14’ [one week after avalanche] – In the interval since I began writing we have packed up our traps and are on our way down - actually I am sitting in a sheltered nook above that little patch of vegetation by the stream above Chobu [village], & it is raining softly which many account for some curious mark on the paper. I don’t want you to think dearest that I am in perpetual gloom over the accident. One has to wear a cheerful face & be sociable in a company such as we are. But my mind does go back very often to the terrible consequences of our attempt with great sadness.

I think it would be a good thing to send a copy of my narrative to a few climbing friends. Claude, to show to his climbing party, David & Herbert Reade. It won’t be of great interest to people who aren’t climbers I should suppose, but one might be circulated to my family too if you think they would like it. I have written to my father & to Geoffrey Young, Younghusband (very briefly) & Frank Fletcher. Please also send the account to Farrar asking him to read it and send it back to you (I don’t much want it to become an official document in the A.C., or at least not yet). And in circulating the narrative you will quote my remarks on p. 7 between marks //.

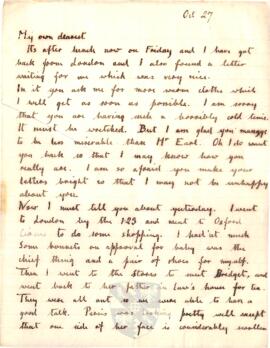

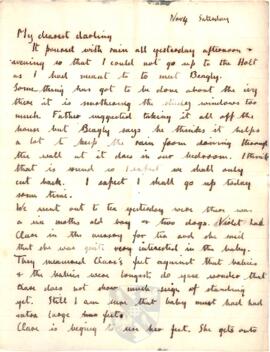

I don’t know whether you will have got the hang of our plans & arrangements. The reason for going to Kharta is really that the General wants to see that part of the country; the excuse that we want to collect flowers & birds & beasts. I had the chance of going back straight from here, but the chance of seeing the early flowers over the other side was too good to be missed & I’m still hoping to get back after a week or ten days there by a short cut through the corner of Nepal which would be a very interesting journey though extremely wet & should land me in Darjeeling before the middle of July. However that depends much on transport arrangements & I want to get someone to come with me who understands these lingos- perhaps Norton. My possible dates for leaving Bombay are 22nd, 29th July and 1st and 5th of Aug. I shall avoid the 29th if possible as it is a small boat P&O & I would sooner take the Trieste boat on the 1st & come overland. The 22nd is too early in all probability & the 5th (also P&O) is the best boat they have which is a consideration when meeting the monsoon. If I come by P&O I shall probably come to London; anyway I’ll wire giving simply a date (i.e. that of leaving Bombay) and write or wire again from Marseilles or Venice. I’ve been thinking much since your last letter dated April 22 etc. what we would like best to do in early autumn. PyP [Pen-y-Pass] is always attractive & it would be a very pleasant little party; I think we must wait to fix that if we feel like it. Prima facie I’m more in favour of breaking new ground & Richmond in early September might be perfect if Mill [Ruth's sister Mildred?] wants us. I suppose Bob has a job at Catterick; lucky man; he might teach me to fish in those dale streams. I’ve always wanted to go to Richmond.

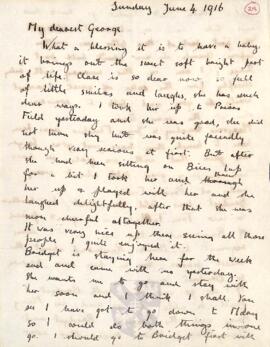

I’m glad you like the book on botany & find it helpful; we shall be too late to make much use of it together this year, but it’s a thing we must do together sometime – I mean to learn much more about flowers for our children’s sake if for no other reason. But there is another reason; - there is a little shrub in front of me now most prettily blooming with a pink flower, not unlike a rather stiff & thorny rosemary, only the flower is more chartered - which I should much like to introduce into our garden but I can’t tell it’s species.

We are in much reduced company now - Strutt, Longstaff, Finch, & Morshead went off to Darjeeling retracing our steps, about a week ago, & Norton, G. Bruce to Kharta, where we shall rejoin them. I’m much distressed about Morshead’s hands. I fear he’s certain to lose at least the tips (i.e. 1st joints) of 3 fingers on the right hand; & he had a good deal of pain too. G.B. [G. Bruce] writes that his toes are troublesome, but no great harm was done there, & Norton, who was quite knocked out by our climb & a dispirited man after it he has now discovered that what he thought were bruises in the soles of his feet are really frostbite & bad enough to prevent him walking seriously. My finger has almost recovered except for a black nail, so I got off very lightly.

I must finish this off for a mail which is to go off at once. Please give my love to your Father & Marby [written up the side margin:] and make the understand as far as possible about the accident. Many hugs and kisses to the children and endless love to you dearest one. Your Loving, George.